Making life simpler, easier and less stressful. Aren’t these a big part of what good design can do to help us live well?

Designing Simplicity was the first in a series of Inspire + Connect evening events organised by the Design Council Challenges team.

The speakers were Sam Hecht, co-founder of Industrial Facility, whose ethos of striving for simplicity has led to more user friendly products, and Dan Thompson, founder of the Empty Shops Network, and the instigator of the recent #riotcleanup efforts in London.

Sam talked about his design process - removing unnecessary layers so that the function of an object is simple and clear. But he also recognised that everything is a product, that every product is part of a system, and that every system exists in an environment.

The design does not stop at the edges of the object, but is an extension of the whole.

Dan is not a designer, but he facilitates activities and change by the simplest means possible. In the case of #riotcleanup, an idea, a mobile phone, a twitter account, a memorable hashtag and a broom.

In the first 24hrs of #riotcleanup, 87,000 twitter followers believed that they could make a difference. The key was simplicity - a straightforward, practical action using basic equipment meant a low barrier to entry.

Both speakers demonstrated that a structured approach to designing simplicity can produce incredibly effective results.

Observations on the underlying structures of communication design: cognition, composition, organisation, construction.

Wednesday, 14 September 2011

Monday, 12 September 2011

Rhetorical images

Rhetoric is the art of using language for the purpose of persuasion – to effectively convey the ideas of the speaker to their audience.

But how can you structure an image communicate a message?

As a communicator, you can still apply the four classical rhetorical methods (known as tropes) to the way you design with images;

Presentative images

Presentative images are used when you want to show what something looks like, or to highlight certain features. The image is a literal representation of the subject matter.

Raising a presentative image to the rhetorical level requires some imagination. Vehicle images or packshots of computers are a classic example. The skill lies in the arrangement of the various components, choice of the right background, dramatic lighting or coloured gels, use of a wide-angle lens or a low camera angle. A hand holding the object gives an idea of scale. All these methods are ways of bringing the object to life.

Metonomy

You can make abstract concepts comprehensible to your audience by using the principle of metonomy. By creating a closeness between an abstract concept and a concrete idea, the latter is made to stand for the former. Examples in rhetorical terms might be the UK government represented by the street sign for Whitehall, or the idea of freedom being represented by an image of the Statue of Liberty.

Synecdoche

Rhetorical substitution, synecdoche, indicates something by having the part standing for the whole. For example, a stethoscope image can be used to represent a doctor (or a hospital). As the viewer engages with the image, they create the entire medical profession in their imagination.

Synecdoche is also used to prove that a visual message is relevant to its subject. By placing an object in its natural context, the viewer sees both the part and the whole together, and the message carried by the object is reinforced. For example a stethoscope around the neck of a figure in scrubs suggests a doctor. Because the two parts of the image support each other, the viewer is reassured that the entire message is believable.

Metaphors and similes

To help others to understand your message, you can use comparative language to illustrate, reinforce or clarify your point. Metaphors suggest similarities between things by substitution, for example, stating that something is something, whilst similes suggest something is like something.

For example, advertisers tend to use metaphor or similie in promoting alcoholic drink brands, because the rules on what you can claim for your product are very strict. Using visual metaphor or similie allows sophisticated brand characteristics to be quickly established in the mind of the audience.

In practice

It is possible to use all four tropes for the same topic, depending on your intended message.

For instance Land Rover (for no other reason than I like Land Rovers);

But how can you structure an image communicate a message?

As a communicator, you can still apply the four classical rhetorical methods (known as tropes) to the way you design with images;

- The presentative image shows

- Metonymy illuminates

- Synecdoche indicates

- Metaphors and similes compare

Presentative images

|

| iPad 2 ad - presentative image |

Raising a presentative image to the rhetorical level requires some imagination. Vehicle images or packshots of computers are a classic example. The skill lies in the arrangement of the various components, choice of the right background, dramatic lighting or coloured gels, use of a wide-angle lens or a low camera angle. A hand holding the object gives an idea of scale. All these methods are ways of bringing the object to life.

Metonomy

|

| Whitehall sign - metonomy image |

Synecdoche

|

| Stethoscope - synecdoche image |

Synecdoche is also used to prove that a visual message is relevant to its subject. By placing an object in its natural context, the viewer sees both the part and the whole together, and the message carried by the object is reinforced. For example a stethoscope around the neck of a figure in scrubs suggests a doctor. Because the two parts of the image support each other, the viewer is reassured that the entire message is believable.

Metaphors and similes

|

| Guinnness 'Surfer' ad - similie |

For example, advertisers tend to use metaphor or similie in promoting alcoholic drink brands, because the rules on what you can claim for your product are very strict. Using visual metaphor or similie allows sophisticated brand characteristics to be quickly established in the mind of the audience.

In practice

It is possible to use all four tropes for the same topic, depending on your intended message.

For instance Land Rover (for no other reason than I like Land Rovers);

|

| Presentative image shows (the whole) |

|

| Metonomy image illuminates (an aspect of the subject) |

|

| Synecdoche image indicates (by using a part of the whole) |

|

| Metaphor and similie compares (an attribute of the subject) |

Tuesday, 6 September 2011

Grids

|

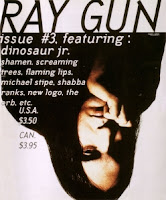

| RayGun magazine cover |

Carson’s method is to design every page from scratch, reading the magazine article and trying to make sure that the content is interpreted in the page design. He believes that over-reliance on a grid can lead to laziness, as designers accept the pre-formatted settings in their software and produce bland layouts.

“I can’t work with any kind of guidelines on the computer – the first thing I do is eliminate them… I never learned what a grid was… and didn’t see a place for them in my work.”

David Carson

|

| Vormgivers exhibition poster |

Modernist typographer Wim Crouwel sits at the opposite end of the design spectrum. The grid methodology has underpinned his work for the last half century and still makes sense to him today.

Wim’s working method relies on a rigorous hierarchical analysis of text and image. This structured approach to the relative positioning of elements on the page inevitably led to his use of a grid as the primary method of arranging content, and for providing the reader with access to it.

“I was called “gridnik” because all the time I was talking about grids and giving lectures about them.”

Wim Crouwel

Two great designers, two different approaches.

Personally, I love using grids. The point of them is to provide a structure within which a designer or typographer, sometimes working in a collaborative team, can arrange content.

It provides a rational basis on which a set of recognisable typographic conventions can be arranged, creating a consistent pattern that allows the reader to navigate content with clarity.

As a device, the grid can be as simple as a single page-sized cell, or as complex as Karl Gerstner’s ‘perfect’ 58-unit grid for Capital.

|

| Karl Gerstner's 58-unit grid |

Where the content is continuous text, a simple single column structure is all that is required, but in a more complex magazine format, a grid structure with the flexibility to accommodate more complex and varied material will be needed.

The starting point for both types of grid is the content type and the choice of typeface, size and leading. The logic of the grid structure can then be developed in relation to the format.

Creating a grid

Geometry and mathematics are, broadly speaking, the two approaches to creating a grid.

Geometrical grids are based on the golden section (1:1.618), a ratio of width to height. This approach is typically seen in book publishing.

Mathematical (or modular) grids are based entirely on the logic of the page and type size. This approach is one of the characteristics of the International Typographic (Swiss School) style of design.

The golden section

Traditional book page design works with a pair of facing pages with margins and content arranged according to the golden section (1:1.618). The geometry of the page requires no calculations, the positioning of elements being derived from the size and shape of the pages themselves. This approach works well for single or double columns of type, but is less successful for more complex layouts.

Fibonacci sequence

An alternative geometrical approach is to use the Fibonacci sequence of numbers to establish margins. The relative proportions are inner margins of 3 units, top and outer margins of 5 units and a bottom margin of 8 units.

Width to height ratio (‘A’ sizes)

The ISO ‘A’ series of paper uses a ratio based on a series of root two rectangles, where each rectangle has the same width to height ratio if halved. The starting point is the A0 size of paper, with each subdivision exactly half the size of the previous size.

Modular grid

A modern basic grid subdivides the page into a number of smaller fields or modules. Vertically the page is split into margins and columns, generally measured in millimetres, whilst horizontally the page is divided by the baseline grid, measured in points or millimetres. The text baseline grid combined with the number of columns on the page determines the size and shape of the modules in the grid.

The choice of grid methodology to use depends on the nature of your project, the type of content and your own working methods.

“The grid system is an aid, not a guarantee. It permits a number of possible uses and each designer can look for a solution appropriate to his personal style. But one must learn how to use the grid; it is an art that requires practice.”

Josef Müller-Brockmann

More terrific grid-centric articles can be found at The Grid System, an ever-growing resource where graphic designers can learn about grid systems, the golden ratio and baseline grids.

Tuesday, 30 August 2011

Wayfinding

Like a story, all navigation has a beginning, middle and end.

Engaging in any new environment – a report, a website, a transport terminal - people need to feel confident that they know where they are and where they are going. Using signposting to connect people to a real or virtual place gives them a sense of control over their immediate environment.

Good wayfinding makes a difference

Successful wayfinding projects identify key decision points along a route and provide signage or pointers so that the traveller can predict what lies ahead and make informed decisions.

By signposting clear routes through a space using designs that are in sympathy with the environment, you create easy to follow paths for the traveller to follow. Places that have some sort of visual context, one that provides additional structured meaning and functionality to directional signage, delivers a more enjoyable (and informative) user experience.

Consistency of language is important, especially if the traveller may engage with signage at any point in the system. And the sequence in which the traveller encounters information, and how specific that information is, is key.

Decisions, decisions...

First of all you need to know where you are starting from – a contents page or homepage; perhaps a car park or a plaza. Secondly, you want to know the general direction of travel to your primary destination. As you get closer, the signed information becomes more location specific and there are perhaps options for secondary destinations within the immediate vicinity – for example boxouts or features in a publication; cafes or toilets in a mall.

Thinking about these decision points – the points in the journey where a traveller will have questions, what sort of questions they will be and how the questions might be answered effectively – provides a structured sequence in which travellers encounter a seamless experience from the start of their journey to the finish.

Some decision point solutions adopt a zonal system, for example station signage with generic signs in the outer zone and more specific platform information in the inner zone. Other solutions use a point-to-point system, for example trails or cycle routes where each sign hands off to the next.

But too many signs can create confusion. Minimise the decisions your traveller has to make by sticking to the 7 +/-2 magic number (and always ask the question of whether a sign is in fact necessary at all).

Legible London

For example, the Legible London street signs and maps pilot is aimed at helping people find their way across London on foot. The sign system replaces existing maps at transport interchanges, such as bus stops and tube stations, and also appears on cycle hire docking stations.

By fixing the location in geographic space and providing local detail, alongside clear directions to destinations further afield, the wayfinding system encourages people to walk and to explore their local environment.

An additional benefit is that on average one Legible London sign replaces two pieces of redundant signage.

So whilst the setting often provides the framework for signage, the principles of wayfinding are about defining activity, ensuring a consistency of language and expressing information with character in order to create lasting connections between visitor and place.

Engaging in any new environment – a report, a website, a transport terminal - people need to feel confident that they know where they are and where they are going. Using signposting to connect people to a real or virtual place gives them a sense of control over their immediate environment.

Good wayfinding makes a difference

Successful wayfinding projects identify key decision points along a route and provide signage or pointers so that the traveller can predict what lies ahead and make informed decisions.

By signposting clear routes through a space using designs that are in sympathy with the environment, you create easy to follow paths for the traveller to follow. Places that have some sort of visual context, one that provides additional structured meaning and functionality to directional signage, delivers a more enjoyable (and informative) user experience.

Consistency of language is important, especially if the traveller may engage with signage at any point in the system. And the sequence in which the traveller encounters information, and how specific that information is, is key.

Decisions, decisions...

First of all you need to know where you are starting from – a contents page or homepage; perhaps a car park or a plaza. Secondly, you want to know the general direction of travel to your primary destination. As you get closer, the signed information becomes more location specific and there are perhaps options for secondary destinations within the immediate vicinity – for example boxouts or features in a publication; cafes or toilets in a mall.

Thinking about these decision points – the points in the journey where a traveller will have questions, what sort of questions they will be and how the questions might be answered effectively – provides a structured sequence in which travellers encounter a seamless experience from the start of their journey to the finish.

Some decision point solutions adopt a zonal system, for example station signage with generic signs in the outer zone and more specific platform information in the inner zone. Other solutions use a point-to-point system, for example trails or cycle routes where each sign hands off to the next.

But too many signs can create confusion. Minimise the decisions your traveller has to make by sticking to the 7 +/-2 magic number (and always ask the question of whether a sign is in fact necessary at all).

|

| Legible London street sign © TfL |

For example, the Legible London street signs and maps pilot is aimed at helping people find their way across London on foot. The sign system replaces existing maps at transport interchanges, such as bus stops and tube stations, and also appears on cycle hire docking stations.

By fixing the location in geographic space and providing local detail, alongside clear directions to destinations further afield, the wayfinding system encourages people to walk and to explore their local environment.

An additional benefit is that on average one Legible London sign replaces two pieces of redundant signage.

So whilst the setting often provides the framework for signage, the principles of wayfinding are about defining activity, ensuring a consistency of language and expressing information with character in order to create lasting connections between visitor and place.

Friday, 19 August 2011

The sound of 100,000 people chatting

|

| Listening Post |

Entering a darkened space, you find the work flashing and flickering as texts appear and disappear over grid of over 200 small electronic screens. There are seven ‘scenes’ and at intervals there is darkness and silence before Listening Post enters the next cycle of movement.

The sampled words and phrases are accompanied by ambient mechanical sounds. Combined, the work produces a form of mechanical poetry or music. The result presents a ‘sculpture’ of the ‘content and magnitude’ of online chatter.

"By sampling text from thousands of online forums, Listening Post produces an extraordinary snapshot of the ‘noise’ of the internet, and the viewer/listener gains a great sense of the humanity that sits behind the data. The artwork is world renowned as a masterpiece of electronic and contemporary art and a monument to the ways we find to connect with each other and express our identities online." Curatorial statement

|

| We Feel Fine |

But whilst Listening Post has an air of industrial dystopian menace it is essentially passive. The ability to interact with the data in We Feel Fine presents a friendlier, more inclusive view of online chat.

Friday, 5 August 2011

Flatplans

|

| Credit: Diane Parkin |

Using a flatplan allows the editor to quickly see where there are clashes between similar types of article and where additional content is required (or where content may need removing).

Different levels of readership can also be established in the flatplan. Content intended for a general audience, perhaps at the section starts, and those parts for a specialist audience, perhaps placed deeper in the publication.

An appropriate structure for the different content types should be provided (using the LATCH model) to offer the viewer multiple levels of understanding in the most accessible way.

Consideration by the designer of what organisational precedents have already been set, and how the viewer might be expecting to access the information based on their previous experiences, indicates the likely choice for an appropriate editorial structure.

Using a flatplan to provide a pattern (or flow) to the communication at document level, allows information at the story level to build up to a series of ‘destinations’ within the document where decisions can be made (using the AIDA model). In laying out content, a designer should work closely with an editor to establish the flow of the material. This helps to retain the readers attention, creates interest in the subject matter and directs the reader through the information to the call to action.

This principle also works in film. To maintain interest, most films have an invisible narrative structure composed of three, five or seven acts leading to the finale. Each builds up to a ‘destination’, generally a point in the film where a main character makes a decision that alters the course of the narrative. This can be expressed as a flatplan of storyboard frames on a timeline.

[Spoiler alert] For example in Danny Boyle’s Sunshine, the key destination points are Capa’s decision to alter course to rendezvous with Icarus I; his realisation that there is an unknown person aboard Icarus II; and his escape from the airlock to detonate the Stellar bomb.

And you can apply the same narrative structural principles to books, TV, Radio, games...

Tuesday, 2 August 2011

Scanpaths

Our eyes don’t read in a continuous steady line, but scan for information and look for patterns in a series of rapid left to right skips and pauses, known as saccadic movement.

In order to read efficiently, you recognise word shapes. As you read, you don’t look at individual characters. Instead your eyes scan the x-heights across the word and your brain compares the shape of the word outline with words in your memory, skipping over unfamiliar wordshapes, but creating comprehension based on the context of the surrounding words.

We do this because reading each individual letter in a word would be too time-consuming. Instead the eye moves and pauses as it looks for familiar patterns along a line of text.

The point where the eye pauses is called a fixation, whilst the regressive movement between points is called a saccade. A sequence of fixations and saccades across a design is called a scanpath. (Generally speaking, the number of fixations and saccades and length of time a reader spends on them indicates the relative readability of a typeface.)

In western society, by habit we start reading top left and finish bottom right, so these two areas of the page assume special significance for placing important information. Dominant fixation points like this are known as ‘hotspots’. Placing important information at these points, for example headlines top left, or calls to action at bottom right, help in the exchange of key information.

Research indicates that the human eye has the tendency to follow the same scanpaths when encountering familiar media, so in this situation a designer can place unexpected details or incongruous imagery in the design to create new hotspots to attract the readers attention.

The practical application of this insight is that careful placement of different content types can help lead the readers eye around a page or screen, create interest and/or understanding and improve the structural hierarchy of the communication.

In order to read efficiently, you recognise word shapes. As you read, you don’t look at individual characters. Instead your eyes scan the x-heights across the word and your brain compares the shape of the word outline with words in your memory, skipping over unfamiliar wordshapes, but creating comprehension based on the context of the surrounding words.

We do this because reading each individual letter in a word would be too time-consuming. Instead the eye moves and pauses as it looks for familiar patterns along a line of text.

The point where the eye pauses is called a fixation, whilst the regressive movement between points is called a saccade. A sequence of fixations and saccades across a design is called a scanpath. (Generally speaking, the number of fixations and saccades and length of time a reader spends on them indicates the relative readability of a typeface.)

In western society, by habit we start reading top left and finish bottom right, so these two areas of the page assume special significance for placing important information. Dominant fixation points like this are known as ‘hotspots’. Placing important information at these points, for example headlines top left, or calls to action at bottom right, help in the exchange of key information.

Research indicates that the human eye has the tendency to follow the same scanpaths when encountering familiar media, so in this situation a designer can place unexpected details or incongruous imagery in the design to create new hotspots to attract the readers attention.

The practical application of this insight is that careful placement of different content types can help lead the readers eye around a page or screen, create interest and/or understanding and improve the structural hierarchy of the communication.

Labels:

Cognition,

Communication,

Composition,

Message,

Text

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)